Campus in a Forest

Reed Hilderbrand developed this essay in collaboration with Mark Hough, University Landscape Architect at Duke, to celebrate ten years of work together on campus. During this time, Reed Hilderbrand has been guided by two themes Mark has championed — the improvement of facilities that enhance student life and a renewed stewardship of and engagement with the Duke’s unique cultural and natural landscape.

ORIGINS

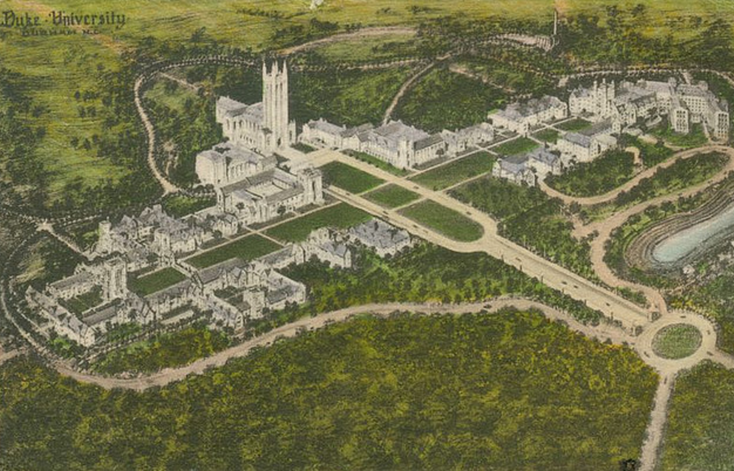

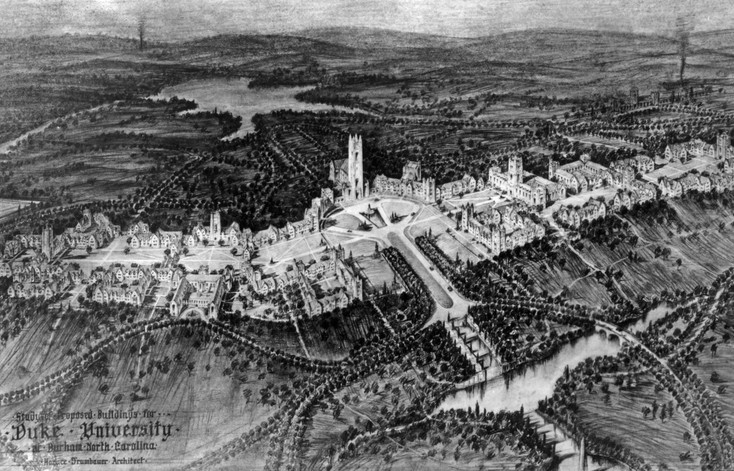

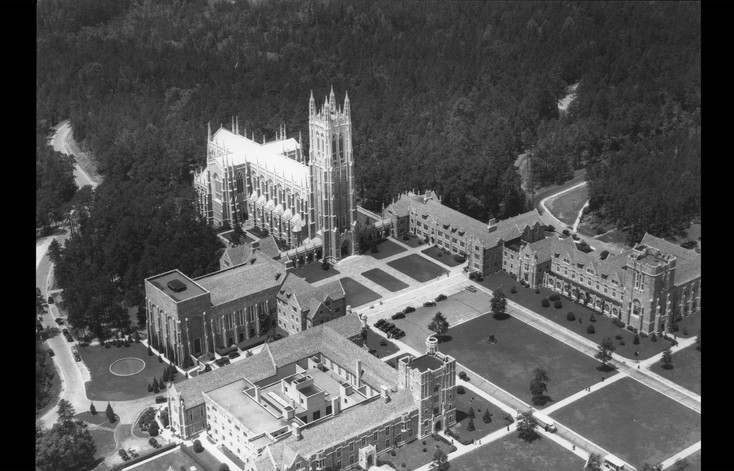

Duke University’s iconic campus emerges at a moment in history when American universities are building expansive, ambitious landscapes across the continent. Duke’s aspirational image of a Gothic “campus in the forest” suggests a place set apart from a workaday world, where a civilized nature forms the background to a contemplative and creative sanctuary for life and learning.

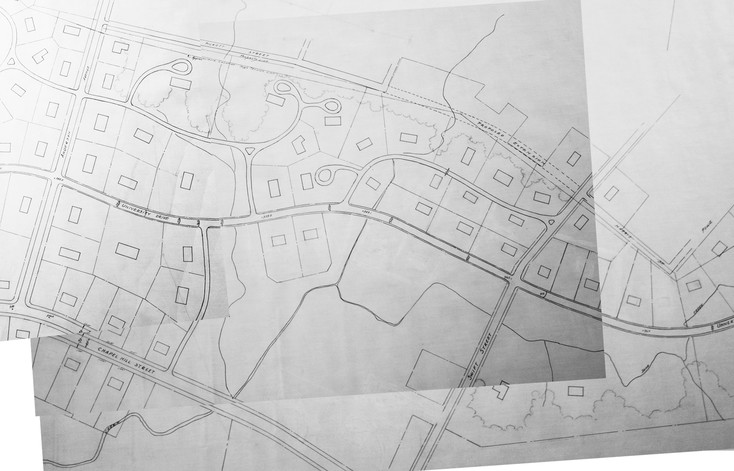

Olmsted Brothers partner Percival Gallagher, along with architectural collaborators Horace Trumbauer and his lead designer, Julian Abele, helped guide the design of Duke’s two linked campuses. The team’s initial schemes reflected varied ways to reconcile the building program with topography, hydrology, and the native regrowth forest. They settled on an image of the campus as a cloistered quadrangle, sequestered from the surrounding landscape but highly imageable and filled with symbolic references to European and American campuses.

In these idealized plans, campus boundaries were seen as fixed and protective. Today, as we engage more fully the wider world beyond the edges of campus, boundaries have become dynamic, negotiated conditions, often characterized by permeability and overlap. At Duke, this means continued work in the drainage ways and cultivated edges of the forest landscape.

TRANSFORMATIONS

Expansive growth in the second half of the twentieth century altered the balance between campus and forest.

Today, with a renewed focus on the environment as an ecological and experiential resource, Duke is investing in a reciprocal relationship with its waterways and naturalized hollows.

In the later years of the twentieth century, Duke’s development as a leading national research university required several new building campaigns, especially around West Campus, with significant expansion of the medical center and the professional schools. Stormwater runoff from an increase in impermeable surfaces led to diminished ecological health in the hollows drainage ways. Fragmentation of the forest and hollows systems followed.

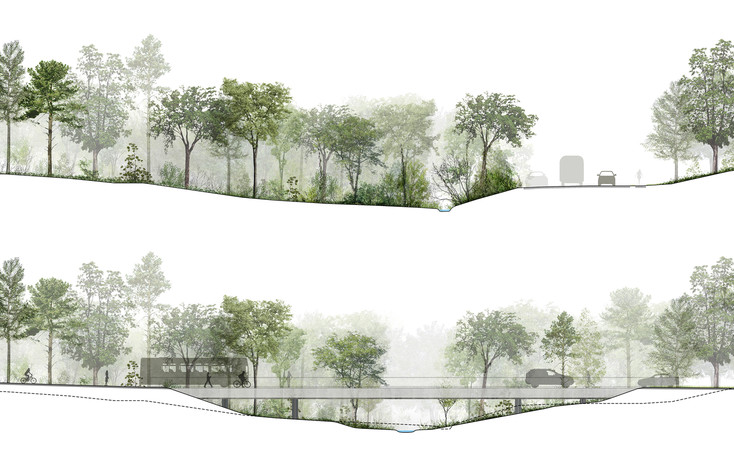

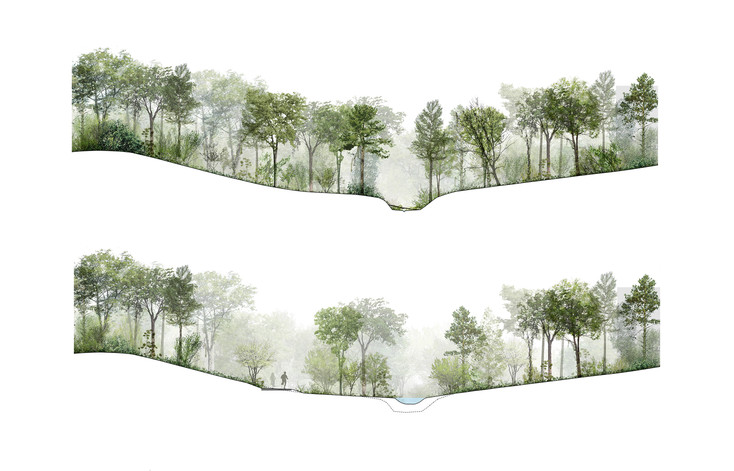

A series of studies over the last ten years has conceived a renewal of Duke’s natural systems and forest cover. Among these, Reed Hilderbrand’s master plan for Campus Drive and Arts Campus focused on renewal of the landscape between East and West Campuses. A new hub for the arts is envisioned, siting program expansion within the ridge and valley pattern of the hollows, restoring forest edges and drainage systems between quads, rehabilitating the waterways with new bridges replacing culverts, and increasing habitat diversity along with campus community occupation.

Along with these efforts, the inclusion of outdoor sculpture within the Arts Campus is seen as part of a larger effort to increase student and community use of the Campus Drive network of walks and trails. This evolution returns to the earlier vision of Duke being strongly tied to the experience of its land resources.

COMMUNITY

A newly revitalized West Campus student life precinct celebrates the juxtaposition of stewardship and innovation, carefully situating contemporary interventions that support today’s diverse campus culture alongside the revered historic setting of West Union and West Quad.

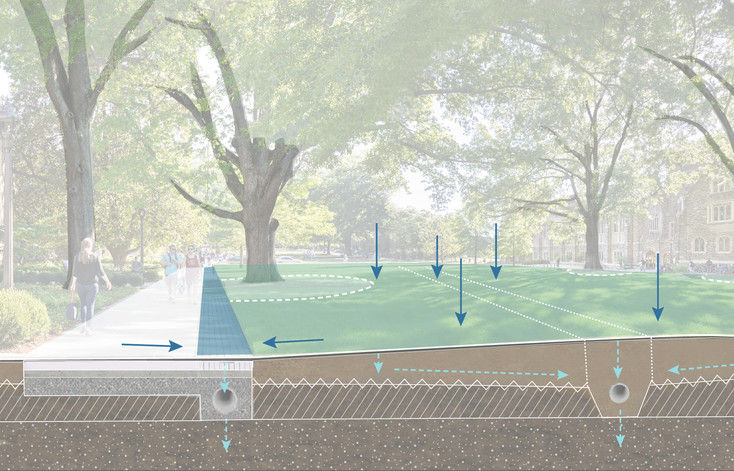

Over the decades since its completion in the 1930s, West Quad became a place for celebration, recreation, and the occasional student protest. More frequent and intense usage of the quad by students, along with maturation of its hardwood population, led to notable decline of the Quad’s trees and its soil resources. Revitalizing its broad lawns and grand oak canopy required a holistic approach to horticulture and soils management and the technologies of soil moisture and drainage. A renewed commitment to stewardship ensures that the cherished tree canopy, seasonally changing understory, and rich ground cover vegetation are maintained and protected for future generations. At the renewal project’s culmination, Duke renamed the Quad after Abele, one of the nation’s notable twentieth-century African American architects.

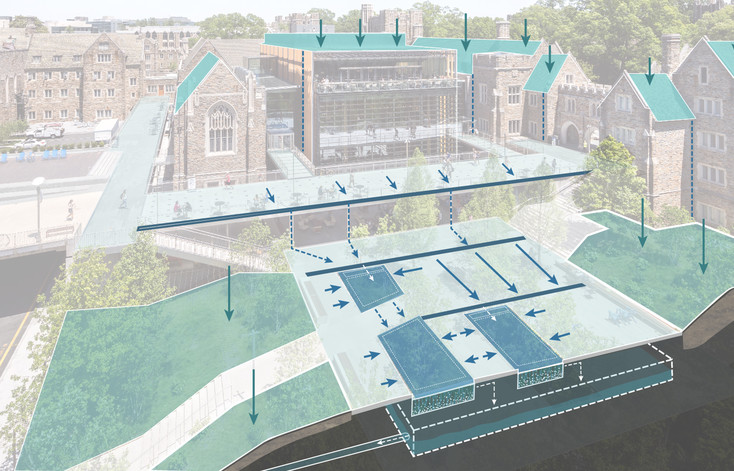

Beginning with the creation of a lively gathering terrace outside the Bryan Center a decade ago, a sequence of expansive new landscape spaces has shaped the student life precinct, creating a network of indoor- and outdoor-program sites that support community and academic enrichment, large events, and informal gatherings. The most iconic of these is Crown Commons, which transformed an underutilized courtyard and service area into a distinctive contemporary plaza adjacent the new Brodhead Center. The vibrant outdoor living room and dining spaces promote engagement and activity while helping to achieve Duke’s ambitious goals for resilience and sustainability.

KEY FACTS

- There are 35 different species of plants in the beds around West Union and Crown Commons, including red twig dogwoods, sweet bay magnolias, Carolina silverbells, bald cypress, and a variety of oaks. Species native to North Carolina make up a majority of the plant palette.

- Over 85 trees were planted as part of this work. The largest were the mature bald cypresses planted in the paved Crown Commons terrace. These were craned into place.

- While the tree openings around the bald cypresses look small, they conceal a structural grate designed to cantilever past the concrete base beneath the pavers. Roots have sufficient soil volume for the trees to thrive over a long period of time. Approximately 2,550 cubic feet of soil is available to each bald cypress.

- The high number of trees and shrubs planted around the West Union and Crown Commons extends the unique “campus in a forest” condition into the plaza itself. As the plants mature, they will become part of a larger campus canopy that provides comfortably shaded paths and outdoor spaces throughout the University.

- Working in conjunction with sustainable design features of the Brodhead Center building, the Crown Commons landscape directs stormwater runoff from the surrounding roofs and paving into specially designed planters that filter and infiltrate the water. Following a rain event, the sound of moving water is audible within the recessed garden planting, much as you might hear in the nearby forest hollows.