State of City Soils

The city subsurface is mysterious and remote, but it’s not unknowable. Principal Eric Kramer and Stephanie Hsia spent a summer examining the soils of Boston’s urban parks.

This ongoing research effort by Reed Hilderbrand and Halvorson Design Partnership has examined soil health in Boston’s urban parks to understand why trees thrive in some sites and fail in others. Reed Hilderbrand published an interim report on the project for the 2014 Annual Conference of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). The Boston Society of Landscape Architects (BSLA) have subsequently honored the effort with a 2015 Honor Award.

Landscape architects are dedicated to planting trees in the city, but the modern city is not necessarily hospitable to growing trees. In response, we have come to rely on numerous technical strategies to sustain urban trees and the soils that support them. More often than not, however, our discipline installs trees, and hopes for the best. Rarely do we analyze the relative outcomes of our choices of soils, pavement details, tree species, and management practices.

In our practice, we strive to find the most robust planting systems available. How amazingly planting systems and understanding of urban soils have evolved in the last ten years. We now manufacture soils to exacting specifications. We place them in distinct profiles with drainage and aeration infrastructure. We exactingly measure how pavements transfer the weight of urban traffic to the soils to manage the compaction that restricts root growth and shortens the lives of urban trees. Yet much debate remains within the profession. And still, there’s much more to learn.

Soils and trees are dynamic systems, changing and evolving over time. Because they are below pavements, in most cases, we cannot know how these novel systems change and mature. We can’t see the roots, so we don’t know how well they are utilizing the soils we have placed and if critical biological communities that support nutrient transfer to the roots are forming naturally. And while we can make visual assessments of how well our trees are performing, we can’t easily compare that to how well they might be growing in alternative circumstances.

We are left with many questions: How does a practitioner make choices between competing planting systems, some patented and marketed, others custom-designed and needing specialized soils engineers? How do we better educate our clients about the value of their investments below grade? And do we direct cities and maintenance staffs to manage their piece of the urban forest for highest performance and greatest longevity?

The Study

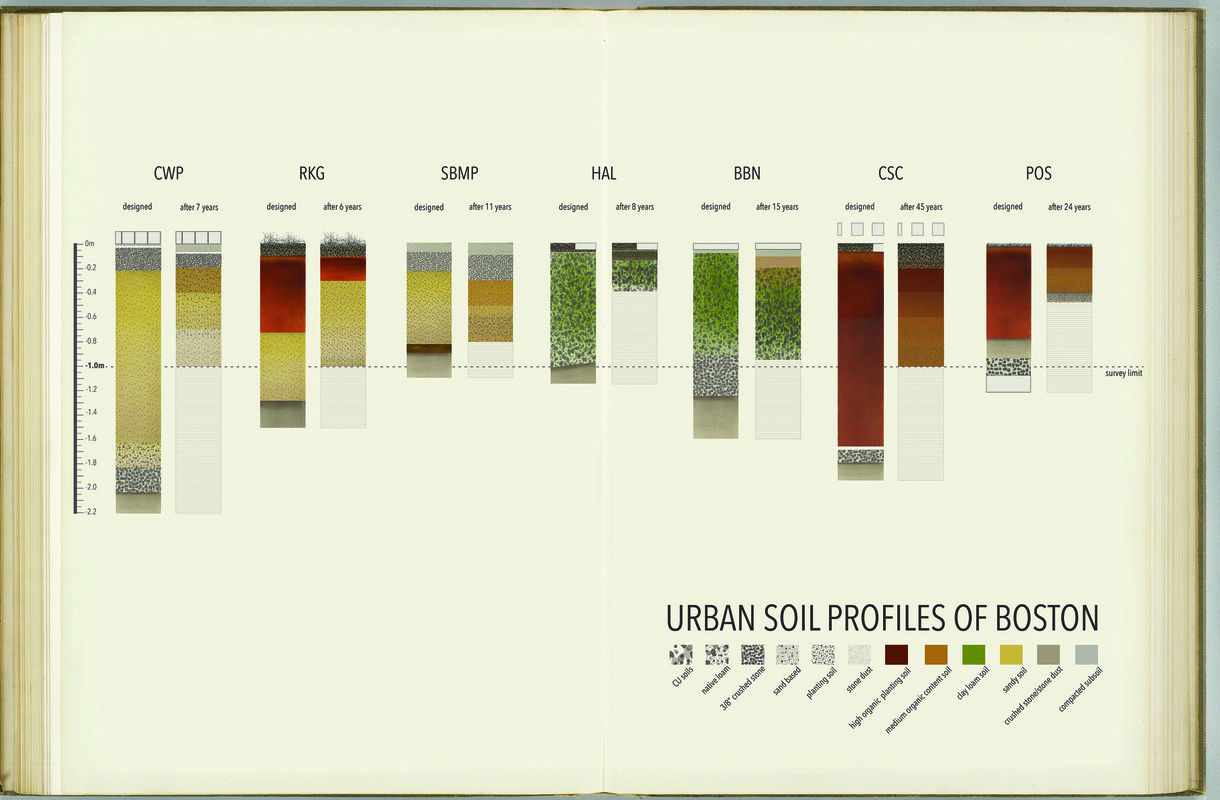

This project is a comparative study of urban tree plantings that have endured Boston’s population and elements for between 5 and 45 years. We want to understand how the trees have grown, how the soils have matured, and how the paved surfaces around the trees have weathered over the years. Our goal is not to crown one of the competing planting strategies superior to others, but to understand the dynamics of these complex systems, including what we can’t normally see below grade.

What we illustrate here is also the result of more than five years of discussion and investigation. Chris Moyles and I have led panel discussions at ASLA Annual Meetings on various subjects related to urban manufactured soils, urban tree health, and the management and maintenance of urban landscapes. Gary Hilderbrand has directed research studios on the planting of half a million trees in South Boston. Of course, finally, as practitioners, we believe strongly in the cultural and ecological benefits of the urban forest, specifically the power of shade in the city. We engage in the practical realities of urban tree planting on a daily basis.

We are joined in this project by a great team that includes practitioners and scientists. Robert Uhlig, president of Halvorson Design Partnership, a firm which has executed many iconic public landscapes in Boston, has been integral to uncovering the history and details of a number of our study sites. Bryant Scharenbroch, from the Morton Arboretum in Chicago, our lead researcher, developed our testing methods and led our fieldwork in June. And Kelby Fite, of the Bartlett Research Labs, is building our analytics related to tree health and management practices, linking the science with our collective practice. It is also my great pleasure to credit the incredible intelligence and tenacity of Stephanie Hsia, a 2014 summer intern for Reed Hilderbrand, and a 2015 MLA candidate at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Stephanie managed the Boston-based field work, the gathering of base information, and the initial illustration of findings.

Field Work

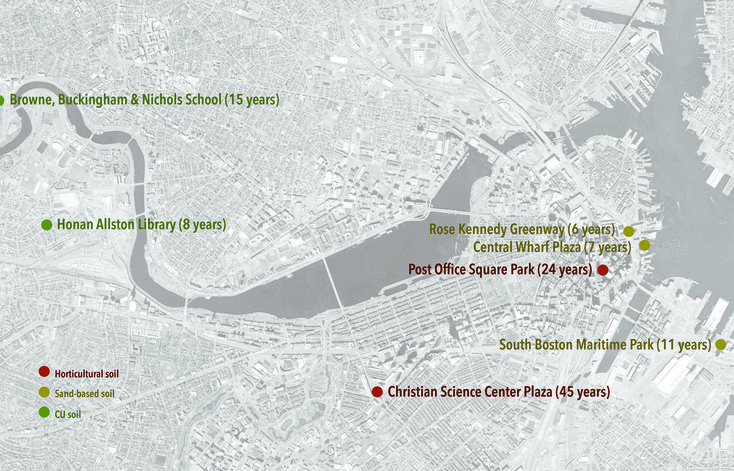

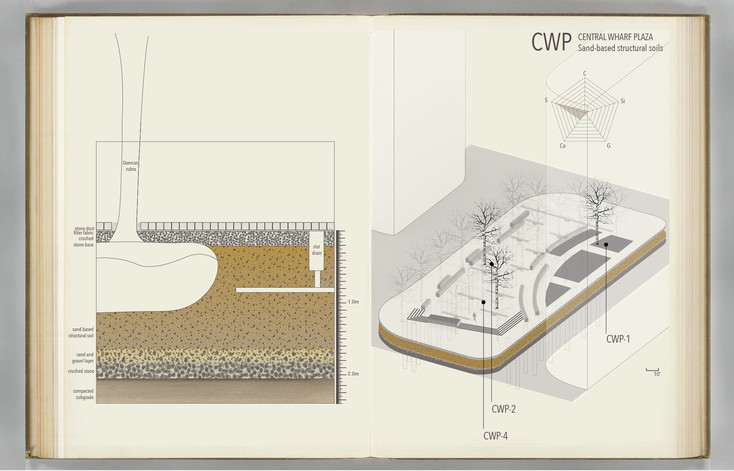

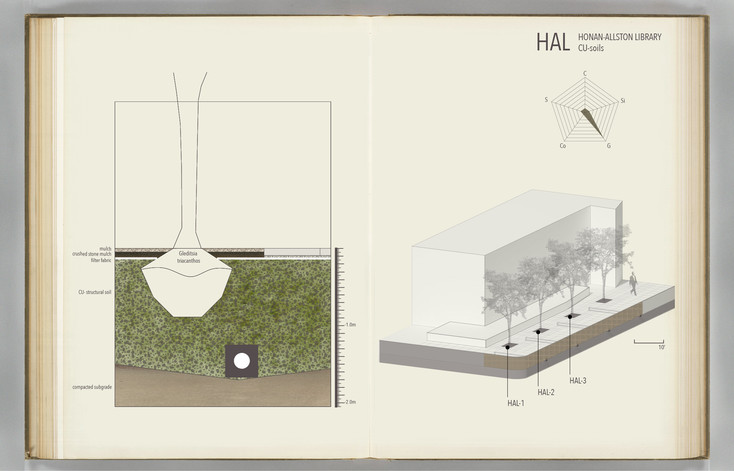

On June 11, our full team conducted a reconnaissance of an initial list of survey sites in Boston. Our survey sites included: three sites with sand-based structural soils (Central Wharf Plaza, South Boston Maritime Park, and Rose Kennedy Greenway), two sites with a soils-system pioneered by Cornell University (Buckingham, Browne and Nichols School and Honan-Allston Library), one site with suspended pavement (Christian Science Center Plaza), and one site with native loam soils (Post Office Square). Preliminary work enabled our understanding of where soil sampling could be accomplished and to identify barriers to soil extraction.

On the following two days, Bryant, Kelby and Stephanie returned to each site to make the full assessment. At each site, we sampled three trees of varying condition and situation to capture the potential diversity of the subsurface. We identified a location approximately 0.7 to 1.0 m away from each tree so sampling would occur within the drip line of each tree but outside the original root ball, and extracted up to one meter of the soil profile with a soil augur. For half of the sites, the soil profiles stopped well in advance of one meter, either reaching refusal (the point at which it becomes too difficult to extract with hand tools) or compacted subgrade. We took weight measurements and samples at 3 to 4 horizons, thus producing a total of 79 soil samples. Soil characterization such as texture, structure, density, and microbial biomass and respiration are currently pending.

To evaluate tree planting response such as growth rate, internode growth, and overall health to soil conditions, we extracted tree cores and noted tree health using a qualitative methodology developed by Jerry Bond of Urban Forest Analytics. Site characteristics and distances to potentially influencing land uses such as roads and buildings were also recorded.

We will conduct a comparative analysis across the different sites to better understand how these soil systems have influenced tree growth. The seven sites range from six to forty-five years old, raising the question: how does age impact urban soil formation and what does soil succession look like within these different systems? Maintenance practices such as irrigation, fertilization, and tree care contribute to soil development. Through this study, we might be able to ascertain ideas for maintaining and assessing long-term sustainability for each system.

Regardless of how much we are able to conclude or compare between the soil systems, the study will contribute to widespread understanding of how these widely used public spaces, some beloved, function over time. The trees we observed in the best condition were little-leaf lindens in the 45-year old suspended pavement system at the Christian Science Center. We observed significant organic matter present in the top layer of the soil profile. Whether by design or not, large gaps in the suspended concrete pavement system have enabled leaf litter to accumulate and break down into the soil. The pavement system was allowing a process that happens with soil development in the forest, to occur in the city.

The city subsurface is mysterious and remote, but it’s not unknowable. Peeling away the layers of the city floor to examine the media that sustains Boston’s tree canopies—the defining character of our urban experience—opens up new thinking about how life above and below our streets must correspond.

All photography courtesy of Stephanie Hsia. All drawings © Reed Hilderbrand LLC Landscape Architecture.